This article has been published in Notes & Queries, by Oxford University Press.

Marland, R. (2022) On Sarah Bernhardt’s cancelled production of Oscar Wilde’s ‘Salomé’, Notes & Queries, 69, 350–4, doi:10.1093/notesj/gjac118

Sarah Bernhardt (c. 1880). Image: Paris Musées.

In late June 1892 the Lord Chamberlain’s Examiner of Plays, Edward Smyth Pigott, declined to licence Sarah Bernhardt’s planned production in London of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. Details of how the play would have been staged are limited. This has led to much debate about how – or even if – the Dance of the Seven Veils, a centrepiece of the play, would have been performed. Conversely, assumptions about casting, though supported only by circumstantial evidence, have hardened into facts. Here I note previously overlooked sources that speak to both of these points.

The description of the Dance of the Seven Veils in Wilde’s script is famously brief: ‘salomé danse la danse des sept voiles’.Joseph Donohue (ed), The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 5: Plays, Vol. 1: The Duchess of Padua; Salomé: Drame en Un Acte; Salome: Tragedy in One Act (Oxford, 2013), 549.804. The freedom that Wilde gifted readers and, later, stage directors to imagine the dance for themselves also obscured whatever might have been his own vision. Wilde’s friend and literary executor Robert Ross left the only clue of any substance when he averred, five years after Wilde’s death, that the author had not wanted ‘anything in the nature of Loie Fuller’s performances’.Robert Ross to Gwendolyn Bishop, 6 April 1905, quoted in William Tydeman and Steven Price, Wilde: Salome (Cambridge, UK, 1996), 29–30. Fuller had achieved prominence in Paris in the 1890s with her ‘serpentine dance’, in which she manoeuvred large veils using hand-held poles while illuminated by coloured lights; she devised Salomé choreographies in 1895 and 1907.Megan Girdwood, Modernism and the Choreographic Imagination: Salomé’s Dance After 1890 (Edinburgh, 2021), 34.

Robert Ross claimed that Wilde did not want Salomé to dance like Loïe Fuller. Image: LOC. See also a poster advertising Fuller’s Salomé dance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rodney Shewan has noted that Wilde’s stage direction calling for the dance was inserted in the script at the proof stage, only days after Bernhardt’s production had been cancelled and Salomé was ‘now a closet drama’.Rodney Shewan, ‘The artist and the dancer in three symbolist Salomes’, Bucknell Review, xxx (1986), 102–30, 124; cited in Nicholas Frankel, Oscar Wilde’s Decorated Books (Ann Arbor, 2000), 60. See also Joseph Donohue (ed), The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 5: Plays, Vol. 1: The Duchess of Padua; Salomé: Drame en Un Acte; Salome: Tragedy in One Act (Oxford, 2013), 347–8. However, as Wilde remained confident that the play would be staged in France in October,Maurice Sisley, ‘La Salomé de M. Oscar Wilde’, Le Gaulois, 29 June 1892, 11. ‘Les Théatres’, Le XIXe Siècle, 6 July 1892, 3. he was likely adapting his text for a different rather than a replacement audience. Before he had interested Bernhardt he had hoped to cast ‘an actress who was a first-class dancer’, and attempted to make contact with an acrobat he had seen dancing on her hands at the Moulin Rouge,William Tydeman and Steven Price, Wilde: Salome (Cambridge, UK, 1996), 19. so he must have begun by thinking of the dance as a crucial component of the staged play. Kerry Powell has argued persuasively that Salomé was written as a vehicle for Bernhardt,Kerry Powell, Oscar Wilde and the Theatre of the 1890s (Cambridge, UK, 1990), 40 ff. and, since Bernhardt was not a dancer, Wilde was either willing to sacrifice dancing for acting proficiency, or, as is suggested by his early pursuit of professional dancers, to entertain the possibility that the dance be performed by a stand-in.

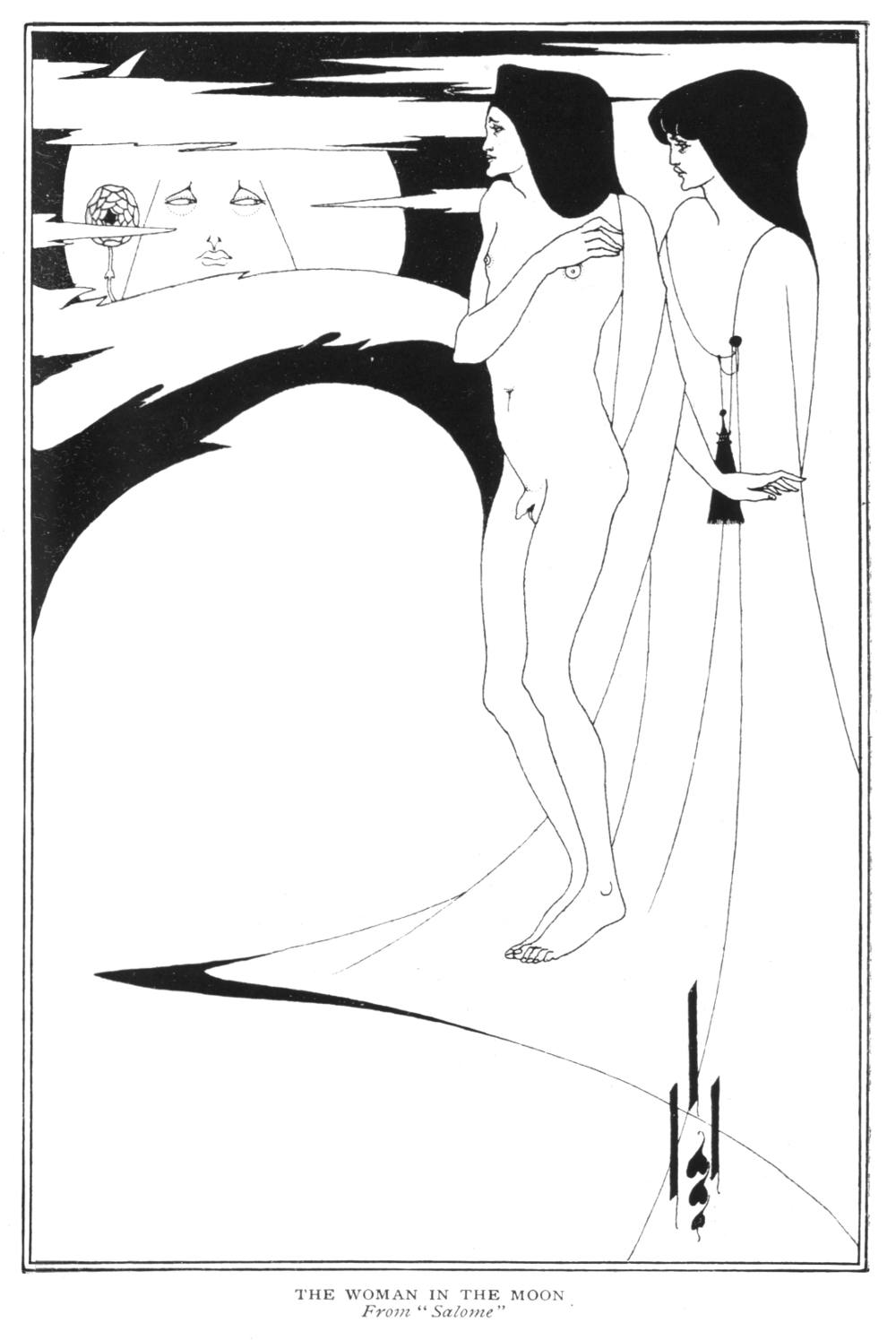

An illustration by Aubrey Beardsley for the first English edition of Salomé. Wilde is depicted as ‘The Woman in the Moon’. Image: gutenberg.org

W. Graham Robertson, who was tasked by Bernhardt with adapting her Cléopâtra costumes to the requisites of Salomé, records in his memoirs that he asked Bernhardt if she planned to have a veiled substitute perform the dance. ‘I’m going to dance myself,’ she insisted. When Robertson asked how, she replied, with an enigmatic smile, ‘Never you mind’.W. Graham Robertson, Time Was (London, 1931), 127. As William Tydeman and Steven Price have remarked, since the production did not go ahead, ‘whatever coup de théâtre Bernhardt had in mind will never be known’.William Tydeman and Steven Price, Wilde: Salome (Cambridge, UK, 1996), 22.

The best indication can be found in an article by Henri Bauër for L’Écho de Paris.Henri Bauër, ‘La Ville et le Théâtre’, L’Écho de Paris, 2 July 1892, 1. The artist William Rothenstein wrote to Wilde shortly after Pigott’s ruling, evidently to ask his friend for further details. Wilde replied: ‘The Gaulois, the Echo de Paris, and the Pall Mall [Gazette] have all had interviews. I hardly know what new thing there is to say.’Oscar Wilde to William Rothenstein, [mid-July 1892], in Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis (eds), The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde (London, 2000), 531–3. Wilde wrote to Rothenstein from Bad Homburg, where he was undergoing a rest cure. He arrived on 7 July and left before 12 August. See Christoph Hamann, ‘Oscar Wilde in Bad Homburg’, The Wildean, xi (1997), 39–41. The Gaulois and Pall Mall Gazette interviews, both published on 29 June 1892, have long been familiar to critics.‘The Censure and “Salome”’, The Pall Mall Gazette, 29 June 1892, 1–2; reprinted with minor variations as ‘The Censure and “Salome”’, The Pall Mall Budget, 30 June 1892, 947. Reprinted in E. H. Mikhail, Oscar Wilde: Interviews and Recollections (London, 1979), 186–9. Cited in Stuart Mason (ed.), The Bibliography of Oscar Wilde (London, 1914), 370–4; Hesketh Pearson, The Life of Oscar Wilde (London, 1946), 228; H. Montgomery Hyde, Oscar Wilde (London, 1976), 140; Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde (London, 1987), 351–2; and Matthew Sturgis, Oscar: A Life (London, 2018), 445. Le Gaulois, 29 June 1892, 11. Translated into English and excerpted in ‘Mr. Oscar Wilde’, The Standard (London, UK), 30 June 1892, 5; Richard Butler Glaenzer, Decorative Art in America (New York, 1906), 147–8; and Mikhail, 189–90. Cited in Ellmann, 352. The Echo de Paris article has been overlooked. Possibly there has been an assumption that Wilde was referring to another familiar article that appeared in the same newspaper on 6 December 1891, although that article, published several months before the suppression of Salomé, makes only passing reference to the play.Jacques Daurelle, ‘Un Poète Anglais a Paris’, L’Écho de Paris, 6 December 1891, 2, 593–9. An English translation of the article is given in Mikhail, 169–71. Bauër does not format his article as a traditional interview but does claim to have spoken with Wilde. Printed on 2 July 1892, it is the only article to which Wilde can be referring.No other articles about Wilde that could be construed as interviews were printed in L’Écho de Paris between 27 June, when the censorship of Salomé was announced in the British press, and 11 August, the last date Wilde could have left Bad Homburg and therefore the last date on which he could have written his letter to Rothenstein. Bauër writes:

... I had not failed to attend a few rehearsals. Alas! I have barely seen Sarah Bernhardt outline the dance of the seven veils, sketch the hieratic attitudes and the voluptuous poses under the polychrome gauzes stretched, by a chorus of ballerinas, above her head; but I listened attentively to the one act play of the beginner in French prose.‘Aussi n’avais-je pas manqué d’assister à quelques répétitions. Hélas ! j’ai à peine vu Sarah Bernhardt indiquer la danse des sept voiles, esquisser ces attitudes hiératiques et les poses voluptueuses sous les gazes polychromes tendues par un chœur de ballerines, au-dessus de sa tête ; mais j’ai attentivement écouté l’acte du débutant en prose française.’

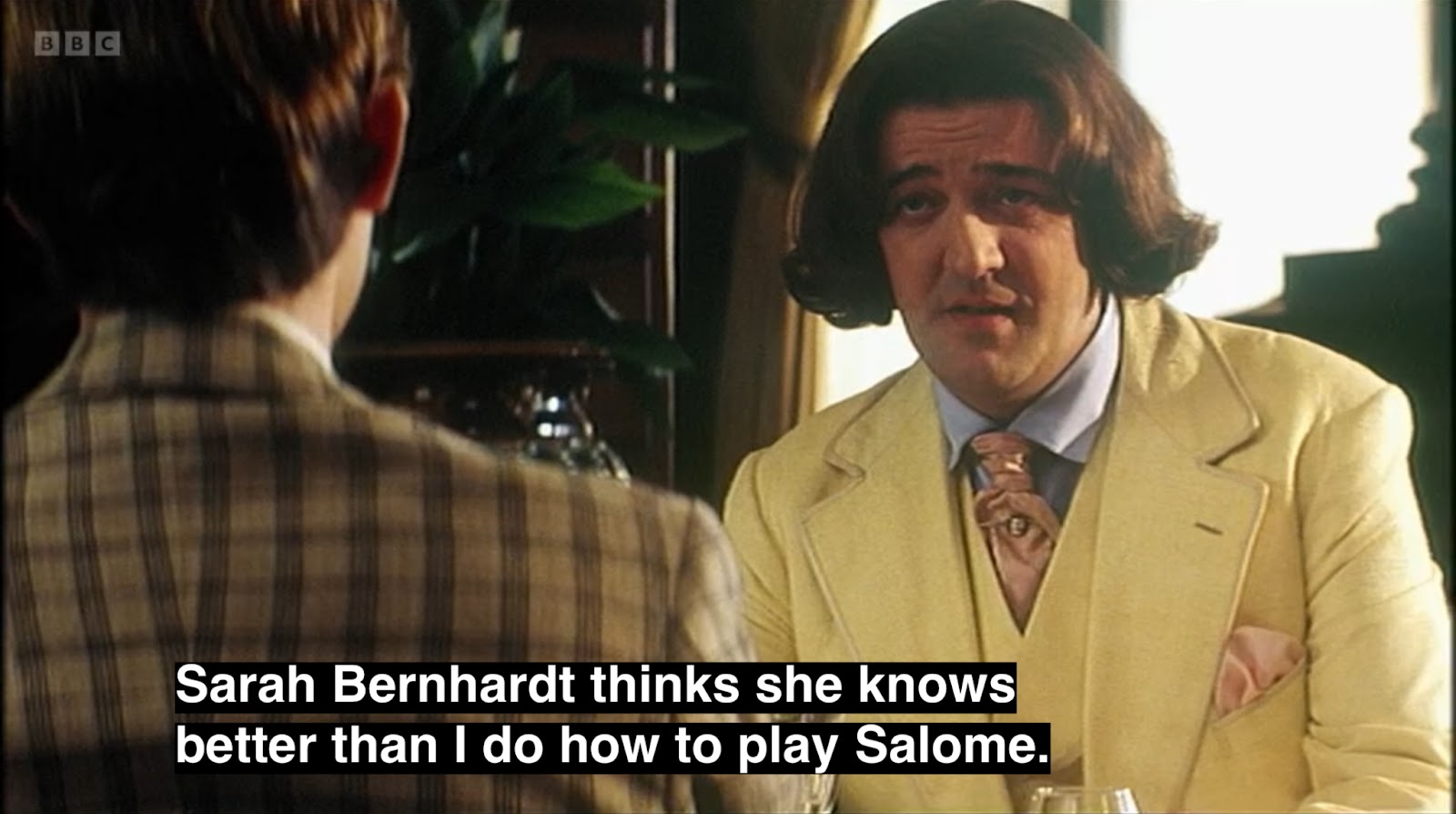

Stephen Fry as Wilde in the 1997 biopic, uncharacteristically complaining about Bernhardt. Image: BBC Films/Capitol Films/Pony Canyon.

Bauër’s account confirms that Bernhardt would have performed the dance. Rather than manipulating the veils herself in the manner of Fuller, she intended to delegate the task to professional dancers. These ballerinas may be the slaves in Wilde’s script who, before the dance, carry on perfumes and the seven veils and remove Salomé’s shoes.Joseph Donohue (ed), The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 5: Plays, Vol. 1: The Duchess of Padua; Salomé: Drame en Un Acte; Salome: Tragedy in One Act (Oxford, 2013), 547.774. The device of having Salomé assisted in her unveiling, common in productions of Richard Strauss’s operatic version of Wilde’s play,William Tydeman and Steven Price, Wilde: Salome (Cambridge, UK, 1996), 162. was therefore a feature of the staging from the outset. Charles Ricketts, with whom Wilde discussed the scenery and costumes of the production, records that, when Wilde first read the script to Bernhardt, she saw that the title role should be performed with ‘no rapid movements; stylised gestures.’‘[P]as de mouvements rapides, des gestes stylisés.’ Charles Ricketts, Oscar Wilde: Recollections by Jean Paul Raymond and Charles Ricketts (London, 1932), 53. Bauër shows that Bernhardt’s plan extended to the dance, with its ‘hieratic attitudes and ... voluptuous poses’. The plan would have played to her strengths, while concealing her lack of dancing skill.

Bernhardt will have exercised complete creative control.W. Graham Robertson, Time Was (London, 1931), 126–7, relates that when Wilde saw Bernhardt being fitted for her costume and noticed that her hair was powdered blue he protested that his script called for Hérodias’ hair to be blue (Joseph Donohue (ed), The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 5: Plays, Vol. 1: The Duchess of Padua; Salomé: Drame en Un Acte; Salome: Tragedy in One Act (Oxford, 2013), 511.37). Bernhardt put her foot down: ‘No, no; Salomé’s hair powdered blue. I will have blue hair!’ Wilde no doubt shared his opinions about the dance, but the final decision was hers. This would have been no different to his experiences staging his other plays both before and after Salomé, where in each case he was obliged to defer to a dominant actor–manager. The dance as conceived by Bernhardt may not have been how Wilde had originally envisaged it but, as he told the interviewer for The Pall Mall Gazette, he had felt ‘pleasure and pride’ at the prospect of Bernhardt, ‘undoubtedly the greatest artist on any stage,’ acting in his play. Katharine Worth has suggested that ‘[p]robably anything she did would have pleased him.’Katharine Worth, Oscar Wilde (London, 1983), 64.

Albert Darmont (c. 1890) in La jeunesse de Louis XIV. Image: Gallica.

The question of who was to act alongside Bernhardt has generally been considered less perplexing. At the time of the 1892 London season Bernhardt’s primary support was the 29 year old Albert Darmont, the latest in a string of younger men to whom she was romantically linked. A number of critics have stated with confidence that Darmont was set to play Hérode, with Tydeman and Price additionally speculating that M. Fleury had been cast as Iokanaan and Jane Méa as Hérodias.H. Montgomery Hyde in Oscar Wilde: The Complete Plays (London, 1988), 26; Kerry Powell, Oscar Wilde and the Theatre of the 1890s (Cambridge, UK, 1990), 45–6; William Tydeman and Steven Price, Wilde: Salome (Cambridge, UK, 1996), 21; Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis (eds), The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde (London, 2000), 529, note 1; and Joseph Donohue (ed), The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 5: Plays, Vol. 1: The Duchess of Padua; Salomé: Drame en Un Acte; Salome: Tragedy in One Act (Oxford, 2013), 468. UPDATE, 21.11.2022: I have now learnt of an earlier critic suggesting that Darmont was to play Hérode: Alan Bird, The Plays of Oscar Wilde, (Plymouth and London, 1977), 59. Darmont may seem the obvious choice for Hérode, the largest role in Wilde’s play, given that he had already appeared in London as Marc Antoine in Cléopâtra, Baron Scarpia in La Tosca, and Loris Ipanoff in Fédora. Yet this would be to assume that Bernhardt always allocated the leading male roles to one particular actor. She did not: MM. Fleury, Rebel, and Munie also appeared in such roles in London.Fleury played Bernhardt’s love interest, François, and Munie her father in Pauline Blanchard; Darmont, who had previously played both roles, did not appear. He was absent again from La Dame aux Camélias, with the part of Armand Duval taken by Fleury. Later in the season, after the cancellation of Salomé, Fleury would appear in Frou Frou as De Valreas alongside Rebel as De Sartorys. Darmont returned to play Hippolyte in Phèdre.

Wilde, in his interview for Le Gaulois, expressed his disappointment that, although Pigott’s decision to prohibit the public performance of his play did not preclude a performance in private,

I could have neither Mme. Sarah Bernhardt nor M. Darmont, a young actor with a great future, to play the two main roles, because they are hired by directors who could not—and I understand it perfectly—lose one or two evenings of receipts.

As the ‘two main roles’ to which Wilde was referring might be assumed to be Salomé and Hérode, this is better – though by no means conclusive – circumstantial evidence that Darmont was earmarked for Hérode.

The matter is resolved by another interview, in this case with Bernhardt and Darmont, published in The Pall Mall Gazette on 6 July 1892.‘The Censorship and “Salome”’, The Pall Mall Gazette, 6 July 1892, 1–2. Critics have been aware of this interview for some time, though at first only as a clipping of unknown origin in the collection of Mary Hyde (later Viscountess Eccles); they have confined themselves to quoting Bernhardt, missing the import of Darmont’s words.Richard Ellmann, 350, cites an ‘unidentified interview with Bernhardt, 8 [sic] July 1892’ that he had found in the Hyde collection: ‘as she [Bernhardt] told an interviewer, Wilde had said the leading part [in Salomé] was that of the moon.’ Ellmann’s source must be the 6 July 1892 article in The Pall Mall Gazette, in which this information features. Bernhardt’s section of the interview has also been quoted by William Tydeman and Steven Price, Wilde: Salome (Cambridge, UK, 1996), 20; Eleanor Fitzsimons, Wilde’s Women (London, 2015), 213; and Sturgis, 455.

‘It is a fine piece,’ he said. ‘I should have liked very much to have created the part of Yokanaan [sic]. Mdme. Bernhardt was to have played Salomé, M. Rebel Hérode, and Mdme Jane Méa Hérodias.’

An argument could be made that Darmont does not state unequivocally that he was cast as Iokanaan, leaving open the possibility that, as much as he might have ‘liked very much to have created the role’, he had been cast in another. This is precluded by Darmont’s following statement that Rebel ‘was to have played’ Hérode. As rehearsals were underway before the cancellation, Darmont must be speaking of the finalised cast.

Albert Darmont (c. 1890) in La jeunesse de Louis XIV. Image: Gallica.

There are several reasons why Bernhardt might have cast Darmont as Iokanaan rather than as Hérode. Firstly, she was in the habit of starring in single-role plays that offered her leading men little opportunity to outshine her.Kerry Powell, Oscar Wilde and the Theatre of the 1890s (Cambridge, UK, 1990), 45–6. Any concerns she may have had that the role of Hérode was too large would seem to be borne out by the first (private) production in England in 1905, the reviews of which treated Hérode as the central figure.Graham Good, ‘Early productions of Oscar Wilde’s Salome’, Nineteenth Century Theatre Research xi (1983), 77–92, 88. Secondly, and more importantly, Darmont was better suited to the role of Iokanaan than Hérode. Reviewers of Bernhardt’s 1891–3 world tour often alluded to the young actor’s attractive appearance. One thought him ‘as handsome as a Greek athlete’, and another that he was ‘much nicer to look at’ than the ‘ordinary French jeune premier’.‘A New Leading Man’, The Sun (New York, NY), 10 November 1891, 3. ‘Sarah Bernhardt’, The Era (London, UK), 4 June 1892, 9. A photograph of Darmont c. 1890 can be viewed at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b531622519 Last accessed 4 November 2022. The New York Times believed that it was his ‘splendid physique’ that had won him the role of Marc Antoine.‘Dusquesne is Discharged’, The New York Times, 10 November 1891, 5. Wilde’s Salomé compares Iokanaan’s hair to ‘clusters of black grapes’: ‘There is nothing in the world that is so black as thy hair’;Joseph Donohue (ed), The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 5: Plays, Vol. 1: The Duchess of Padua; Salomé: Drame en Un Acte; Salome: Tragedy in One Act (Oxford, 2013), 714.301–8. Darmont had ‘loose-curling, jet black hair’,‘Sarah’s Foibles’, The Sunday Times (Minneapolis, MN), 27 December 1891, 12. a perfect fit. Bernhardt may have intuited that by casting Darmont as Iokanaan she would better convince the audience that Salomé’s lust for him is genuine. Later, criticism would occasionally be levelled at operatic productions in which insufficiently alluring performers had been cast in the role.William Tydeman and Steven Price, Wilde: Salome (Cambridge, UK, 1996), 135.

Lewis Morrison, who played Alexis in Vera. Image: NYPL

Bernhardt would have had the final say in casting, but Wilde likely concurred with the choice of Darmont for Iokanaan. Wilde’s first play, Vera; or, The Nihilists, had flopped in New York nine years previously for a litany of reasons that included poor casting.See e.g. [Joe] Howard, ‘Howard’s Gossip’, The Sunday Herald (Boston, MA), 26 August 1883, 9; and ‘New York Theatres’, The Times (Philadelphia, PA), 26 August 1883, 6. For the role of Alexis, Vera’s love interest, Wilde had wanted Kyrle Bellew or Johnston Forbes-Robertson.Oscar Wilde to Richard D’Oyly Carte, [March 1882], in Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis (eds), The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde (London, 2000), 151–2. Joseph Donohue has described Bellew as ‘a well-known actor of heroes and juveniles ... and a very popular ladies’ man’.Joseph Donohue (ed), The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 5: Plays, Vol. 1: The Duchess of Padua; Salomé: Drame en Un Acte; Salome: Tragedy in One Act (Oxford, 2013), 8. Forbes-Robertson, to Wilde ‘a most romantic and beautiful actor’,‘Philosophical Oscar’, The Chicago Times, 1 March 1882, 7. had recently appeared on the London stage as Romeo to Helena Modjeska’s Juliet. Both were appropriate choices, but Marie Prescott, producer of Vera and creator of the title role, plumped for her regular co-star, the 39 year old Lewis Morrison, a well-regarded actor but woefully miscast as the youthful and attractive Alexis. On the opening night, when Prescott exclaimed ‘How beautiful he is!’, the audience roared with laughter at the incongruity of the sentiment and Morrison’s appearance.[?Stephen Ryder Fiske], ‘Spirit of the Stage’, The Spirit of the Times (New York, NY), 25 August 1883, 114. The reviewer may have misheard the line, which in the 1882 script reads: ‘How fair he looks!’ (Josephine M. Guy (ed), Plays IV, The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 11: Plays, Vol. 4: Vera; or The Nihilist and Lady Windermere’s Fan (Oxford, 2021), 123.217). Wilde excised the line in his personal copy of the script, no doubt directly after the opening night. The scene in Salomé in which the princess praises Iokanaan’s body, hair, and lips presents a similar and perhaps even greater risk that Wilde, thanks to his experience in New York, cannot have failed to appreciate.Joseph Donohue (ed), The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 5: Plays, Vol. 1: The Duchess of Padua; Salomé: Drame en Un Acte; Salome: Tragedy in One Act (Oxford, 2013), 523.289–526.338.

The most intriguing result of the discovery that Darmont was cast as Iokanaan is that it recontextualises Wilde’s statement that Bernhardt and Darmont were to play the ‘two main roles’. It now seems clear that Wilde thought of Iokanaan and not Hérode as one of the two main roles. Still, it would be prudent to note that in typically Wildean fashion he also told Bernhardt that ‘the moon played the principal rôle.’The Pall Mall Gazette, 6 July 1892, 1–2.