This article is about Oscar Wilde’s absence from season one of The Gilded Age and was written shortly after the first season aired. I have also written about Wilde’s appearance in season two.

Julian Fellowes, the writer behind Gosford Park and Downton Abbey, has skipped across the pond to bring us a new show: The Gilded Age. Setting his scene in late nineteenth-century New York, Fellowes shows that the upstairs/downstairs divide was by no means unique to Edwardian England.

The Gilded Age follows Bertha Russell (Carrie Coon), who, along with her railroad tycoon husband George (Morgan Spector), has moved into a palatial new home on Fifth Avenue. Agnes Van Rhijn (Christine Baranski) is not disposed to roll out the red carpet for her new neighbours: she belongs to one of New York’s oldest families, and is firmly against the nouveau riche Russells buying their way into high society.

Carrie Coon as Bertha Russell, in a peacock embroidered gown that is less high fashion than Patience cosplay. Image: HBO.

Lady Jane’s over-the-top and utterly aesthetic peacock gown in Patience. Image: LOC.

Meanwhile, Agnes’s niece Marian Brook (Louisa Jacobson) has also relocated to Manhattan. Marian grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania; like Bertha, she must now learn to navigate the strict rules that govern who is “in” and who is “out” of New York’s social elite.

I was excited to discover that The Gilded Age is set in 1882. This is the year that Oscar Wilde embarked on his famed tour of North America. After spending many months immersed in the newspapers of 1882 while researching my book Oscar Wilde: The Complete Interviews, I was looking forward to seeing the era realised on screen.

The show is certainly visually stunning. The upstate New York city of Troy is a convincing stand-in for Fifth Avenue in the early 1880s, and the impeccable costumes would have sent haute couture pioneer Frederick Worth into a frenzy.

Still, a few anachronisms have been allowed to creep in. Marian would have preferred to shop in Ladies Mile, with its huge cast-iron department stores such as Lord & Taylors and Louis Comfort Tiffany’s “Palace of Jewels”, rather than schlepping uptown to patronise poky Bloomingdale’s. And although Thomas Edison’s electrification of a small area of Manhattan in September of 1882 was a spectacle to behold, electric lighting was, by this time, not exactly a novelty: for over a year Charles F. Brush’s arc lamps had been illuminating a one mile stretch of Broadway, and his two massive floodlights in Madison and Union Squares could be seen from sixteen miles away. Oscar Wilde admired Brush’s innovation, declaring that the lights made New York at night as beautiful as Venice.

The Gilded Bubble

These minor inaccuracies do not seriously detract from the show, and can be excused on grounds of poetic licence. More surprising, perhaps, is what has been left out. The characters—rich and poor alike—seem to exist in a bubble. That is, they are insulated almost entirely from the wider culture of the day.

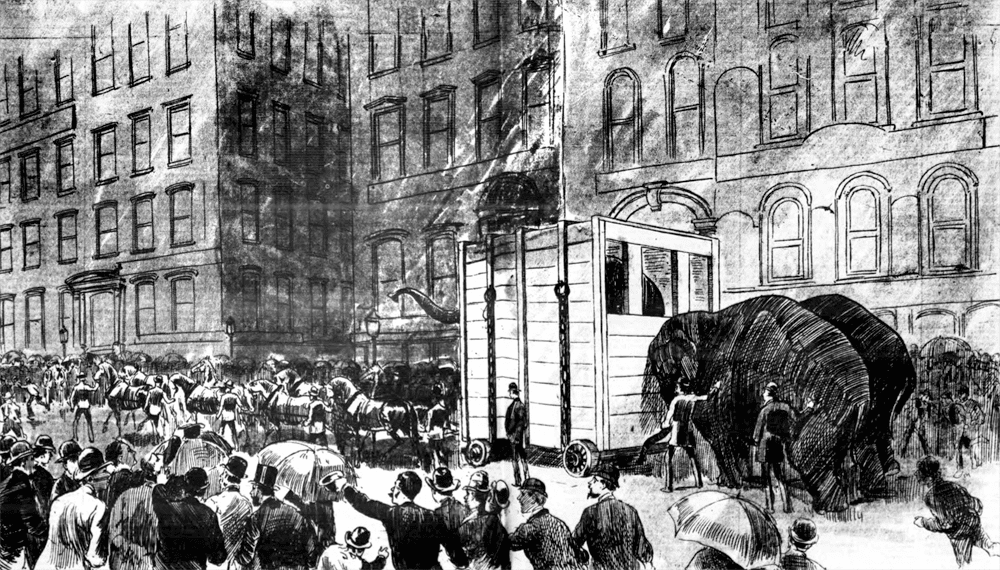

Jumbo the elephant is conveyed up Broadway, a moment not depicted in The Gilded Age. See the full page from the Daily Graphic here.

For example, although George gives a brief nod to the murder of Jesse James, nobody mentions Charles Guiteau, the assassin of President James Garfield whose trial and eventual execution were front-page news for the first half of 1882.

Marian and her admirer Tom Raikes (Thomas Cocquerel), a lawyer who has followed her from Pennsylvania to New York, visit Madison Square and, quite rightly, find there the hand and torch of the yet-to-be-erected Statue of Liberty. But no one takes a trip to Madison Square Garden to see Jumbo, the elephant that showman P. T. Barnum brought to America from London in 1882, sparking a sensation. The steamship Assyrian Monarch arrived in New York with its precious cargo in April (at precisely the time that The Gilded Age begins), but none of our characters are among the crowd of hundreds who saw his wagon conveyed up Broadway by a team of sixteen horses and two smaller elephants.

Marian and Bertha chat amiably in their box at the Academy of Music, but very little is said about the entertainment. Wilde would have approved of this (“If one plays good music, people don’t listen,” says Algie in The Importance of Being Earnest, “and if one plays bad music people don’t talk.”), but in reality music-lovers in New York were ecstatic in early 1882 over the return of Italian soprano Adelina Patti. Very much the Adele of her day, Patti—whose programmes mixed operatic arias with more popular folk ballads—packed out New York’s Germania Theater in February. Wilde had heard her in Cincinnati a week earlier and was not impressed by her rendition of the sentimental favourite “Home, Sweet Home” (he described her rather cuttingly as “a charming music box”), but there is no doubt she was a megastar: the proceeds of her American tour were reported to be $175,000. In the world of The Gilded Age, however, it is as though she doesn’t exist at all.

The Apostle of Aestheticism

Oscar Wilde, photographed by Napoleon Sarony in 1882. Image: LOC.

John Howson as Bunthorne in the American production of Patience. The character was not originally based on Wilde, but Howson’s costume and hairstyle were changed to mimic the Sarony photographs of Wilde.

Perhaps the biggest omission from The Gilded Age is Oscar Wilde himself. Wilde had been brought to America in January by Richard D’Oyly Carte, an impresario every bit as wily as Barnum. Carte was the producer of the immensely popular comic operettas by Gilbert and Sullivan, including The Pirates of Penzance and HMS Pinafore. The duo’s latest effort, Patience; or, Bunthorne’s Bride, was a satire of the aesthetic movement, and Wilde, as a prominent exponent of the philosophy of art for art’s sake, was widely (though incorrectly) perceived to be the inspiration for the foppish poet Bunthorne.

Upon his advent in America Wilde was entertained by influential Manhattan socialites Mrs John Bigelow, Mrs Augustus Hayes, and Mrs Paran Stevens. The political lobbyist and bon vivant Sam Ward took the young man under his wing. Wilde was, like The Gilded Age’s Bertha Russell, an inveterate social climber and would later gain a reputation for snobbishness. His letters home betray his utter glee at how he was being lionised:

I am torn in bits by Society. Immense receptions, wonderful dinners, crowds wait for my carriage. I wave a gloved hand and an ivory cane and they cheer.

But there was also a general feeling that Wilde—who had only a poorly reviewed book of poems to his name and was still a decade away from writing The Picture of Dorian Gray and his smash-hit society comedies—was, like Bunthorne, little more than a charlatan. Journalists wondered whether American hostesses should be opening their doors to the long-haired interloper. No invitations from families in the top tier of New York society, families like the Astors and Vanderbilts, landed on Wilde’s doormat.

The main theme of The Gilded Age—how to gain access to society, or exclude newcomers from it—chimes with Wilde’s own experience of New York in 1882, and he would fit into the show with ease.

Gilding the Lily (and Sunflower)

The Gilded Age does not reference aestheticism at all (Carrie Coon wears a peacock-embroidered gown in one episode, but this is not presented as evidence of her aesthetic tastes). This is a missed opportunity.

Wilde caricatured in 1882. Image: LOC.

Wilde surrounded by admiring young women in aesthetic dress at a reception in New York in 1882. Image: LOC.

Sunflowers and lilies were thought to be the emblems of the aesthetic creed, and Wilde was often caricatured wearing a sunflower on his lapel or carrying a single lily (although there is no evidence he ever did either). As Carte’s assistant, and later wife, Helen Lenoir recalled in 1885:

During [Wilde’s] stay in America sunflowers became quite the rage, and ladies wore them everywhere in public.

No one in The Gilded Age wears a sunflower. Bertha and George’s daughter Gladys (Taissa Farmiga), who spends most of the show’s first season begging her mother to bring her out into society rather than keeping her confined to the family mansion, is precisely the sort of impressionable young woman one can imagine being swept up in the excitement of what amounted to a proto youth culture. A sunflower on her hat would be the least of it. She might even have gone gaga over the dashing Irish poet. As Lenoir noted:

It became the fashion with a number of ladies to follow [Wilde] about, very much in the same way as the aesthetic maidens follow Bunthorne in the opera. They used to throng rapturously around him at receptions; I remember on one such occasion seeing a lady approach him with clasped hands, exclaiming ‘Oh, Mr. Wilde, this is what I have longed for.’

When Wilde was staying in the upscale resort of Saratoga, he was surrounded by a large crowd, mostly made up of women. He told an interviewer about the incident:

I went to the billiard room, but found no refuge there. The women rushed there—ladies in silks, and crapes, and laces, with diamonds in their ears, bringing their daughters with them! To balk the pursuit utterly, I fled to the bar room. Will you believe me that they came there—in 10 minutes, 50 or 100 of them—filling up the place almost. [....] I was stupefied, and said to myself: ‘What land is this I have come to?’

In other words, Wilde was—unlikely as it may seem to us today—an object of female lust.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an American minister and author, penned an excoriating attack on Wilde in February 1882, questioning his masculinity and the morality of his “prurient poems” (Wilde’s own favourite of his poems, Charmides, is about a beautiful youth who ravishes a statue of Athena). Many reporters commented on Wilde’s femininity and made jibes about what they saw as his indeterminate gender, but their mockery concealed their fear that this was precisely what made Wilde so appealing to women. As Gwendolyn in The Importance of Being Earnest points out, men who are “painfully effeminate” tend also to be “so very attractive”.

In a scene in episode five of The Gilded Age, Gladys attempts to sneak out of the house, only to be intercepted at the front door by her mother. What if she were heading to one of Wilde’s lectures on art, or even to a party where he would be present? What if she were clad in aesthetic fashion, with subdued tints and (shock horror) no corset? Gladys can, at times, seem two dimensional. Giving her an interest in popular culture would make her a more rounded and relatable character, and provide further fuel for the parent-offspring conflict. What daughter has never been told: “You’re not going out dressed like that, young lady!”

Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous

In episode eight of The Gilded Age, the penultimate episode of season one, several of the main characters decamp to Newport, another swanky resort favoured by the rich and famous. Wilde was there that summer too. His two week holiday was preceded by a lecture on home decoration in Newport’s casino. He insisted that his principles could be followed by anyone, regardless of their means.

“I am not talking about the houses of millionaires,” he said, but was then interrupted by the entrance of Mr and Mrs Cornelius Vanderbilt. His audience tittered at the timing of the Vanderbilts’ arrival, and Wilde continued as they took their seats: “But I am talking of the houses of those who are not millionaires, if there are any such among you.” The laughter rang out again.

If the lecture was good enough for the Vanderbilts, why not for the Russells? They might even have accompanied Wilde when he was entertained on board the United States warship Minnesota. He joked that dinner should have been served in the rigging, the dishes hauled up by ropes. The diners, “in moments of ennui”, might fire the ship’s guns at the casino.

As a guest character in the Newport episode, and perhaps in one or two earlier episodes, Wilde would have been an excellent addition. But I would go so far as to suggest that he should have played an even larger role in season one, even replacing one of the main characters.

Marrying an Heiress

Blake Ritson as Oscar Van Rhijn, nibbling on a sandwich (not, alas, of the cucumber variety). Image: HBO.

It was when Agnes’s son Oscar arrived that I knew Wilde would not be making an appearance in The Gilded Age. Oscar Van Rhijn (Blake Ritson) is quite obviously based on Wilde. He is a witty young unmarried man who cares little for society’s rules and, as the audience soon discovers, is in a secret relationship with another man. Realising that he will eventually have to marry, he schemes to woo Gladys.

However, it is not Oscar Van Rhijn whom Wilde should replace but Marian’s main love interest, Tom.

Tom Raikes is an enigma of a character. Even though he is a small-town lawyer with no fortune or connections, he is taken up by society as soon as he sets foot in Manhattan. He is a passably good looking chap, but—and let’s be frank—he is rather dull and has less conversation than a pile of rocks. His seemingly effortless ascent to the upper echelons of New York society is inexplicable.

Tom pursues Marian relentlessly, but so too could Wilde. We often think of Wilde as a gay icon, a man who loved the beautiful Lord Alfred Douglas and was condemned to two years’ hard labour for “the love that dare not speak its name”. But it is generally agreed that Wilde did not have his first sexual experience with another man until the late 1880s; up to that point he appears to have been genuinely attracted to women.

In San Francisco he met a young woman known to us only as Hattie (Wilde’s most recent biographer, Matthew Sturgis, suggests that this was Hattie Crocker, the daughter of the director of the Southern Pacific Railroad). He thought she had “the fascination of a panther”, and wrote to her to declare: “Darling Hattie, I now realise that I am absolutely in love with you”. The rumours that Wilde was engaged to Maud Howe, niece of Sam Ward and daughter of Julia Ward Howe, were unfounded, but Wilde’s agent told an interviewer that: “I shouldn’t be surprised if Wilde carried back to England an American girl as his wife.” Wilde’s own brother Willie, when asked what Oscar planned to do for a living, answered: “Oh, he will probably marry an heiress.”

Wilde did eventually marry an heiress, although one with substantially less means than Hattie Crocker, in Constance Lloyd. How intriguing it would have been to see Wilde attempt to court Marian, all the while Gladys is throwing herself at his feet, and Oscar Van Rhijn is looking on with a single raised eyebrow, perhaps seeing something in Wilde that he has yet to sense in himself (we all remember the moment Orlando Bloom’s rentboy clocked Stephen Fry in the 1997 movie Wilde).

Marian’s aunt Agnes, every bit the equal of the formidable Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest, would no doubt have stood in the way of Wilde’s desires, although the pair would have bonded over their shared dislike of the monstrous marble-fronted palaces popping up along Fifth Avenue (Wilde thought the “sham Greek porticos, the Doric chimneys, and Corinthian upper stories” of Fifth Avenue mansions were “so depressing and monotonous”).

Replace Tom Raikes with Oscar Wilde and, I suspect, The Gilded Age would be more entertaining than it already is.

Good Advice

Lillie Langtry, photographed by Napoleon Sarony in 1882. Image: LOC.

All of this wishful thinking is, of course, rather futile: the show has been made and Wilde is not in it.

Wilde noted that: “It is very difficult to give good advice without being irritating, and almost impossible to be at once didactic and delightful.” But if I were silly enough to offer any advice to Oscar-winner Julian Fellowes before he commences work on the next season of The Gilded Age, I would draw his attention to the fact that Wilde’s friend Lillie Langtry, “Professional Beauty” and erstwhile mistress of the Prince of Wales, arrived in New York ahead of her American stage debut in October 1882.

Here’s hoping that Bertha, Marian, et al. will be securing boxes at Wallack’s Theater for what was the highlight of the theatrical season of 1882, and could serve as an effective opening for season two of The Gilded Age.

Update (31 Oct. 2023): Season two began at Easter 1883. Sorry, Lillie.